- Introduction

- Adding Options

- Sample Overview

- Exploring the .NET Standard Library

- Rendering Options in UWP

- Conclusion

Introduction

Just about every app needs a settings screen. A lot of developers choose to simply build-out static UI; hard-wiring buttons and text fields to a setting backing store. If one does this, however, eventually, as the number of settings grows, technical debt increases; making refactoring your settings screen into categories, or changing how the settings are stored or displayed, evermore difficult.

That’s why I built an options system into CodonFX, which integrates with an settings system and an isolated storage backing store, which can be swapped out for a SQLite backing store. The options system in Codon has probably saved me months of development time, and allowed me to do some pretty neat things with little effort, such as exporting and importing options.

Adding Options

With the Codon options system, a single line of code can be used to materialize an option on an option screen that writes itself to a backing store. See the following:

generalOptions.Add(new BooleanUserOption(() => "Boolean 1 title", "Boolean1Key", () => false));

Here we create a BooleanUserOption, which is rendered as a switch on the options screen, and automatically writes its value to Codon’s ISettingsService using the specified string key. The title for the option is a lambda expression, which allows you to easily localize it, so that if the UI language changes the title will be displayed in the correct language.

There are a bunch of built-in option types, representing common setting types, including:

BooleanUserOptionDoubleUserOptionIntUserOptionObjectUserOptionStringUserOption

There are others that are used to present settings in different ways, including:

CommandOptionCompositeOptionListOptionRangeUserOption

CommandOption is used to present a button, that when clicked/tapped executes and ICommand.

CompositeOption allows you to create your own custom behavior with potentially multiple options being rendered in custom UI.

ListOption allows you, for example, to present an enumeration of values that render as a drop down list.

RangeUserOption can be used to present a slider to the user, for writing a double or int value to the backing store.

You can, of course, create custom IUserOption classes, to suite the needs of your application.

Sample Overview

I’ve put together a small sample for UWP to demonstrate it in a UWP app. Codon is cross-platform, and you can see the option’s system in action in apps such as Surfy Browser for Android.

In the sample you see the projects: a UWP app project and a .NET Standard class library. The user options system is located in the Codon.Extras.Core NuGet package, which is referenced by the class library. The UWP app project references the package NuGet Codon.Extras.Uwp.

Exploring the .NET Standard Library

The class library contains various classes including a Bootstrapper class, whose Run method is called when the app starts.

While not absolutely necessary, the AppSettings class has strongly typed properties representing settings, which gives you compile-time confidence that your settings are being referred to correctly.

The partial class located in AppSettings.UserOptions.cs is responsible for registering user options that are presented on the OptionsPage. Generally speaking, the user options represent a subset of the settings.

The ConfigureUserOptions method of the AppSettings class, requires the IUserOptionsService. See Listing 1.

The userRoles parameter is provided just to demonstrate how you might display a different set of options depending on the privileges of the user. This would be more applicable for an enterprise scenario. I do this in one of my apps, and you may not need it.

The IUserOptionsService implementation allows to register multiple option categories, via its Register method. It accepts an OptionCategory method and a list of options that should appear in the category. In some of my apps I display option categories in tabs or sometimes, expandable groups.

When you add an options to a category’s option collection, it is automatically displayed on the options page. Each UserOption object must have a unique key. Lambda expression are used for most of the properties to allow your app to switch languages without requiring a restart.

You can specify a template for the option by setting its TemplateFunc property.

For more information see the UserOptionBase implementations.

Listing 1. AppSettings.ConfigureUserOptions method.

partial class AppSettings

{

public void ConfigureUserOptions(IUserOptionsService userOptionsService, UserRoles userRoles)

{

OptionCategory defaultCategory = new OptionCategory(OptionCategoryIds.General, () => "General");

var generalOptions = new List<IUserOption>

{

new StringUserOption(() => "String 1", String1Key, () => string1DefaultValue),

new BooleanUserOption(() => "Boolean 1", Boolean1Key, () => boolean1DefaultValue)

};

userOptionsService.Register(generalOptions, defaultCategory);

}

}

I mentioned that the AppSettings class is not really necessary. But I like to use it so I can easily refactor the setting names without fear of breaking something.

For completeness I’d like to mention that I use a Resharper live template for defining a setting. See Listing 2. $SettingName$ and $Type$ are the only two editable values. $SettingName$ is defined as ‘Suggest name for a variable’ in the property grid for the template. $Type$ is set to ‘Guess type expected at this point.’

Depending on where you define your AppSettings class, you may want to alter the visibility of the setting name and setter from private to internal or public.

Listing 2. Resharper Live Template for a Setting

public const string $SettingName$Key = "$SettingName$";

static $Type$ $SettingNameLower$DefaultValue = $DefaultValue$;

public $Type$ $SettingName$

{

get => settingsService.GetSetting($SettingName$Key, $SettingNameLower$DefaultValue);

private set => settingsService.SetSetting($SettingName$Key, value);

}

When the app starts up, the Bootstrapper class’s Run method is called via the App class in the UWP app project, as shown in the following excerpt:

protected override void OnLaunched(LaunchActivatedEventArgs e)

{

...

if (!bootstrapperRan)

{

bootstrapperRan = true;

var bootstrapper = new Bootstrapper();

bootstrapper.Run();

}

...

}

Sometimes your bootstrapper may need to go off and perform some asynchronous activity, in which case you’ll want to make the Run method async, and handle errors appropriately.

The Bootstrapper class, registers the AppSettings class as a singleton. See Listing 3.

TIP:Depending on the needs of your app, you may need to implement a platform specific bootstrapper, for each of your platforms. I usually do that, and have the platform-specific bootstrappers call Run on the non-platform-specific bootstrapper.

You may notice in the code that the AppSettings class requires an ISettingsService instance as a constructor parameter. Dependency injection is used to resolve the default instance, using the Codon frameworks default IoC container, the FrameworkContainer class.

In case you’re interested in the Codon framework’s internals, FrameworkContainer locates default type mappings using interface attributes, using Codon’s DefaultType and DefaultTypeName attributes; or the .NET Standard DefaultValueAttribute. If you take a look at the ISettingsService source, you see how it’s decorated with both a DefaultType and a DefaultTypeName attribute. DefaultTypeName takes precedence, and is used to locate a platform specific implementation of the interface, if it exists. If a type identified by DefaultTypeName can’t be located, the container falls back to DefaultType.

We could configure the user options when the AppSettings class is instantiated, which would allow us to pass the IUserOptionsService using DI, but I chose to use an explicit method call since we might wish to postpone configuring the user options to optimize app start time.

Listing 3. Bootstrapper class.

public class Bootstrapper

{

public void Run()

{

Dependency.Register<AppSettings, AppSettings>(true);

var appSettings = Dependency.Resolve<AppSettings>();

appSettings.ConfigureUserOptions(Dependency.Resolve<IUserOptionsService>(), UserRoles.User);

}

}

Rendering Options in UWP

The OptionsViewModel class, in the class library project, contains a Groupings property, which retrieves the UserOptionGroupings from the IUserOptionsService, like so:

public IUserOptionGroupings Groupings =>

Dependency.Resolve<IUserOptionsService>().UserOptionGroupings;

The OptionsPage class exposes an instance of the OptionsViewModel via the IoC container, as shown in Listing 4.

We use both x:Bind and x:Binding expression on the XAML page, and thus the OptionsViewModel instance is exposed both as a property and set as the DataContext of the page. In case you’re not aware, the context of x:Bind is a property of the Page, whereas the good old x:Binding expression uses the Page’s DataContext when resolving properties.

Listing 4. OptionsPage class

public sealed partial class OptionsPage : Page

{

public OptionsPage()

{

this.InitializeComponent();

DataContext = Dependency.Resolve<OptionsViewModel, OptionsViewModel>(true);

}

public OptionsViewModel ViewModel

{

get => DataContext as OptionsViewModel;

set => DataContext = value;

}

}

Within the OptionsPage.xaml file, you see that the page resources include a CollectionViewSource declaration, whose Source property is bound to the view-model’s Groupings property. See Listing 5.

We use a custom template selector to determine the DataTemplate to use for each option in the CollectionViewSource.

Listing 5. OptionsPage Resources element

<Page.Resources>

<CollectionViewSource x:Key="optionsViewSource"

IsSourceGrouped="True" Source="{x:Bind ViewModel.Groupings}" />

<local:OptionTemplateSelector

x:Key="optionTemplateSelector"

Templates="{StaticResource OptionTemplateCollection}">

</local:OptionTemplateSelector>

</Page.Resources>

The OptionTemplateSelector has a Templates property that is bound to a resource located in App.xaml. See Listing 6.

The NamedTemplateCollection includes all the templates, used to display each user option. There is a String template and a Boolean template. The names String and Boolean map to the TemplateName properties of the StringUserOption and the BooleanUserOption class respectively.

NOTE: You can override the template used by a user option by setting its

TemplateNameproperty.

Listing 6. NamedTemplateCollection element

<local:NamedTemplateCollection x:Key="OptionTemplateCollection">

<local:NamedTemplate Name="String">

<local:NamedTemplate.DataTemplate>

<DataTemplate>

<TextBox

Header="{Binding UserOption.Title, Mode=OneWay}"

Text="{Binding Setting, Mode=TwoWay}"

Style="{StaticResource OptionBox}" />

</DataTemplate>

</local:NamedTemplate.DataTemplate>

</local:NamedTemplate>

<local:NamedTemplate Name="Boolean">

<local:NamedTemplate.DataTemplate>

<DataTemplate>

<ToggleSwitch

Header="{Binding UserOption.Title, Mode=OneWay}"

IsOn="{Binding Setting, Mode=TwoWay}"

Margin="{StaticResource OptionItemMargin}" />

</DataTemplate>

</local:NamedTemplate.DataTemplate>

</local:NamedTemplate>

</local:NamedTemplateCollection>

The custom template selector is named OptionTemplateSelector and it sub-classes Windows.UI.Xaml.Controls.DataTemplateSelector. See Listing 7.

The SelectTemplateCore method attempts to retrieve a template whose name matches that of the TemplateName property of the IUserOption. A cache, which is a Dictionary<string, NamedTemplate> is used for efficient O(1) retrieval of templates.

Listing 7. OptionTemplateSelector class

public class OptionTemplateSelector : DataTemplateSelector

{

public NamedTemplateCollection Templates { get; set; }

IDictionary<string, NamedTemplate> cache { get; set; }

void InitTemplateCollection()

{

cache = Templates?.ToDictionary(x => x.Name)

?? new Dictionary<string, NamedTemplate>();

}

protected override DataTemplate SelectTemplateCore(

object item, DependencyObject container)

{

if (cache == null)

{

InitTemplateCollection();

}

if (item != null)

{

var readerWriter = (IUserOptionReaderWriter)item;

var templateName = readerWriter.UserOption.TemplateName;

cache.TryGetValue(templateName, out NamedTemplate keyedTemplate);

if (keyedTemplate != null)

{

return keyedTemplate.DataTemplate;

}

}

DataTemplate result = base.SelectTemplateCore(item, container);

return result;

}

}

Back in the OptionsPage.xml file we see that options are rendered within a ListView. See Listing 8. The ListView is bound to the CollectionViewSource to retrieve its option groupings, and OptionTemplateSelector retrieves the DataTemplate objects for each option.

Listing 8. Options are rendered in a ListView

<ListView ItemsSource="{Binding Source={StaticResource optionsViewSource}}"

ItemTemplateSelector="{StaticResource optionTemplateSelector}"

SelectionMode="None">

<ListView.ItemContainerStyle>

<Style TargetType="ListViewItem">

<Setter Property="HorizontalContentAlignment" Value="Stretch" />

</Style>

</ListView.ItemContainerStyle>

</ListView>

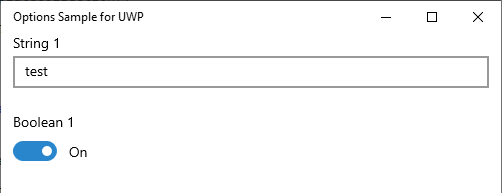

The sample app displays its options as shown in the following figure:

Conclusion

An app’s functionality grows and changes over time. When building a settings screen for your app, it’s prudent to engineer it so that you can easily add settings from the screen without having to spend time re-working the user interface. One way to achieve that is by using a third-party framework like Codon FX, which allows you to add a new user option to your app with a single line of code.

In this article you’ve seen how to configure a .NET Standard project and a UWP app to use Codon FX. You looked at defining an AppSettings class containing settings used throughout your app, and at exposing a subset of those settings as user options.

You saw how to create DataTemplate elements for user options, and at consuming a collection of data templates to render each user option on a settings screen.

I hope you find this article useful. If so, then I’d appreciate it if you would leave feedback below.